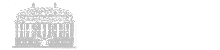

Part 5: Martyrs of the first Christian centuries and the Middle Ages

The period of the Roman authorities (I–IV centuries) persecution against Christians is the one from which date the oldest and most numerous accounts of the holy martyrs. In the Brukenthal National Museum collection, images of the martyrs are found both on altarpieces and in the compositions of small-sized works, generally intended for personal devotion.

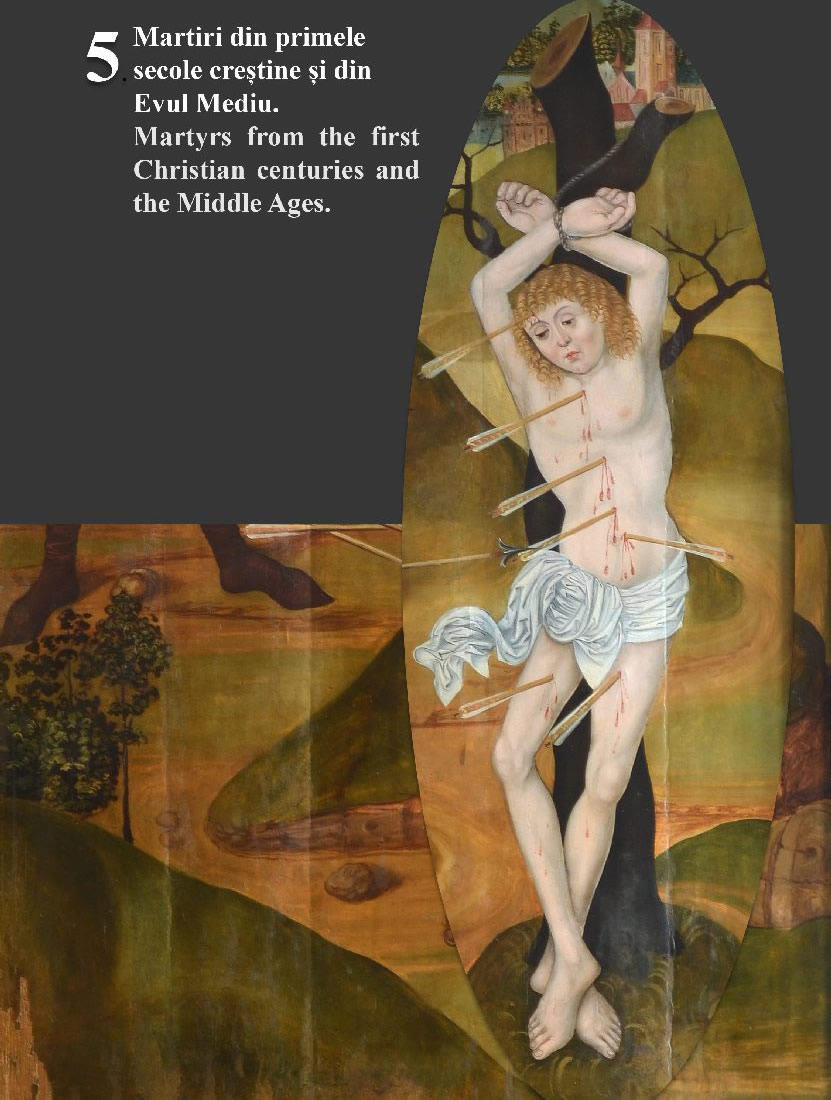

The 10,000 martyrs on Mount Ararat (Fig. 10), killed by crucifixion, are mentioned in the Roman Martyrology on June 22, the basis of this celebration being a legend with many historical inaccuracies and implausible details (possibly the celebration mentioned in the Greek Orthodox Synaxarium on June 1, which refers to the martyrs killed in Antioch, not in the 2nd century but later, in the time of Traianus Decius, 249–251). Representations of the legend were, however, very popular in Renaissance art, such as on one of the Proștea Mare altar’s panels. The composition can also be interpreted in the sense of devotio moderna, actually referring to verifiable historical events, with a great impact on the Saxon rural communities in the Târnava basin: the fortress in the background has been identified with Mediaș, in some interpretations, and the martyrs impaled in the specifically pointed branches of the trees can be linked to the execution commonly applied to his enemies by the voivode Vlad III Țepeș (i. e. the Impaler) of Wallachia, who during 1456–1460 attacked several regions in southern Transylvania, inhabited by Saxons.

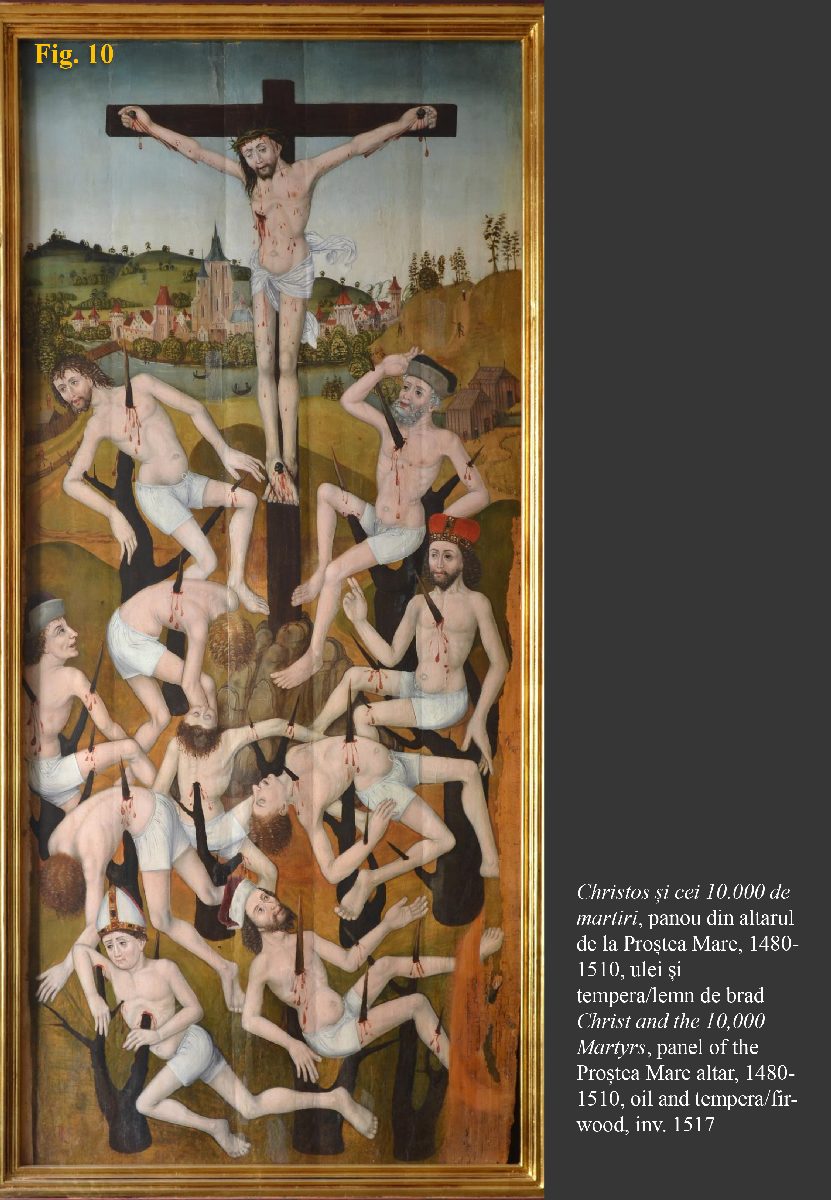

St. Sebastian, St. Irene of Rome and St. Agatha of Sicily (Fig. 11 and 12)

St. Sebastian (ca. 255 – ca. 288) was an officer of the praetorian guard of the emperor Diocletian, accused of treason for releasing Christians from the prison; shot by the archers of Mauretania, he was healed by St. Irene of Rome; admonishing the emperor for his cruelty towards the Christians, he was finally beaten to death with clubs. His cult already existed in the middle of the 4th century, being attested by St. Ambrosius (ca. 339–397), archbishop of Mediolanum.

The martyrdom of St. Sebastian is represented on the right wing of the Proștea Mare altar; in a devotio moderna approach, it explicitly refers to the Ottoman campaign of 1438, led by Sultan Murad II (1421–1444; 1446–1451) and the Tatar archers who supported some Ottoman campaigns against Hungary and, later, the Principality of Transylvania. In the upper left register, voivode Vlad III of Wallachia, known as Țepeș (the Impaler), is represented in a green hat and red collar, as adviser to the sultan, although the one who participated in the campaign was Vlad II Dracul (i. e. the Devil), his father. The explanation for the substitution of historical characters is, without a doubt, the artist's ignorance of the physiognomy of Vlad II Dracul, although he was well acquainted with the physiognomy of Vlad III Țepeș, from the illustrations in the widespread German books about his cruelty.

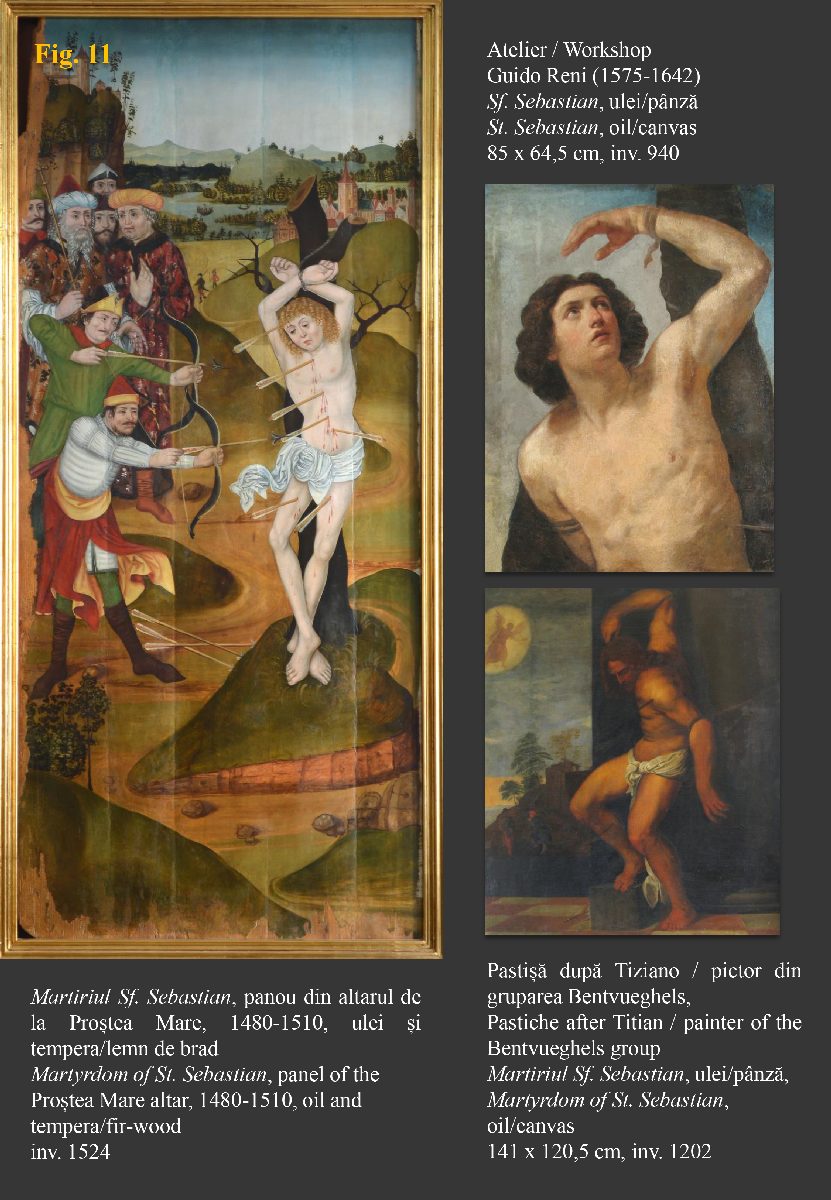

The same subject is to be observed in a pastiche after Tiziano (the altar of the church of Santi Nazaro e Celso in Brescia) – according to Marcin Kaleciński, which may be the work of a painter from the Bentvueghels group (also known as Schildersbent) – according to A. Sonoc, considering the clothing of the characters, similar to that of Flemish genre scenes from the first half of the 17th century. Also, in a somewhat de-contextualized composition, attributed to the workshop of Guido Reni, St. Sebastian is illustrated in a bust rendering, with a single arrow piercing his left side of the torso, the physiognomy reminiscent of that of Antinous, the lover of Emperor Hadrian, according to A. Sonoc.

Also a production of the workshop of Guido Reni (1575–1642), The Martyr’s Death of St. Sebastian renders the saint as a dying man, livid, half-naked, wounded by three arrows removed by St. Irene of Rome († 288), assisted (ahistorically) by St. Agatha of Sicily (ca. 231–251). According to tradition, St. Irene of Rome was the wife of St. Castulus, a martyr, and St. Agatha of Sicily was one of the most venerated virgin martyrs from the time of the emperor Traianus Decius; sentenced to be burned at the stake, her execution was interrupted by an earthquake and died in prison; she was the patron saint of bakers, martyrs and rape victims, the protector against fires, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, easily recognizable by the attribute of the copper cauldron.

It is possible that the two female saints are also represented in the work entitled St. Sebastian, by Francesco Maffei (1605–1660), whose composition is unfinished, a fact that may justify the lack of attributes, the colors of the garments being similar. Thus, the two paintings in the Brukenthal National Museum collection seem to attest an association of the cult of St. Agatha from Sicily with the cult of St. Sebastian, at least in the first half of the 17th century.

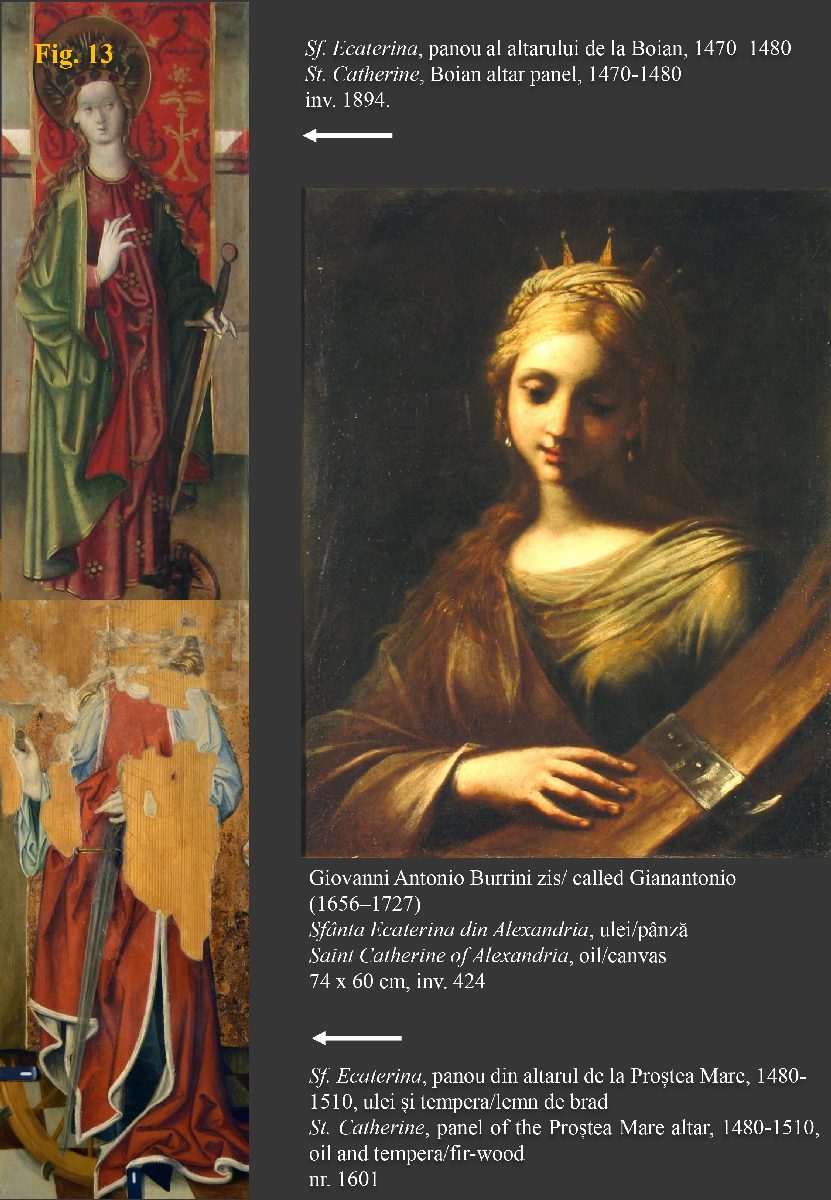

St. Catherine of Alexandria (ca. 287 – ca. 305) was a young scholar, the daughter of a governor of Alexandria (not attested by epigraphic sources), converted to Christianity at the age of 14, following a vision with the Virgin Mary and Child. She offended the emperor Maxentius by refusing to marry him and by choosing to keep her virginity, defeating anti-Christian arguments in a dispute with the philosophers of the imperial court. She was sentenced to death on a spiked breaking wheel but, as a result of the destruction of the wheel, she was beheaded with a sword. The historicity is doubtful, her life being enriched with elements taken from the biography of Hypathia, a scholar from Alexandria, killed by the Christians. That is why, although the Catholic Church initially considered her (but not earlier than the 9th century) as one of the 14 helper saints, after 1969 her celebration was removed from the calendar, becoming optional. She has as attributes the crown, the veil and the implements of execution (the wheel and the sword).

In the collections of Brukenthal National Museum (Fig. 13 and 14), the earliest representations of St. Catherine of Alexandria can be seen on the backs of the Boian altar wing panels (1470–1480) and of the Proștea Mare altar (1480–1510). The attributes of the crown, the veil and the wheel touched tenderly with the right hand, can also be found in the work of Giovanni Antonio Burrini called Gianantonio (1656–1727).

The compositional approach influenced by devotio moderna can be observed in the work of Antiveduto Grammatica (1571–1626), in which St. Catherine wears aristocratic clothes, and the execution instruments consist of a wheel and a double-edged sword dating from the second half of the 15th century.

Also, St. Catherine is depicted from the profile, in the Holy Family painting, copy after a work with several versions made by Polidoro de Rienzo da Lanciano (1515–1565). The other characters are the Virgin Mary, the Child, St. Joseph, and a woman with no attributes. In addition to the significance of the saint’s vision before her conversion, an interpretation in the sense of devotio moderna could highlight the portraits of the donors in the person of Joseph – for the man and of the woman reading – for his wife. Moreover, in the upper left register a river is depicted on the bank of which is a fortified city, the landscape being bordered by high mountains.

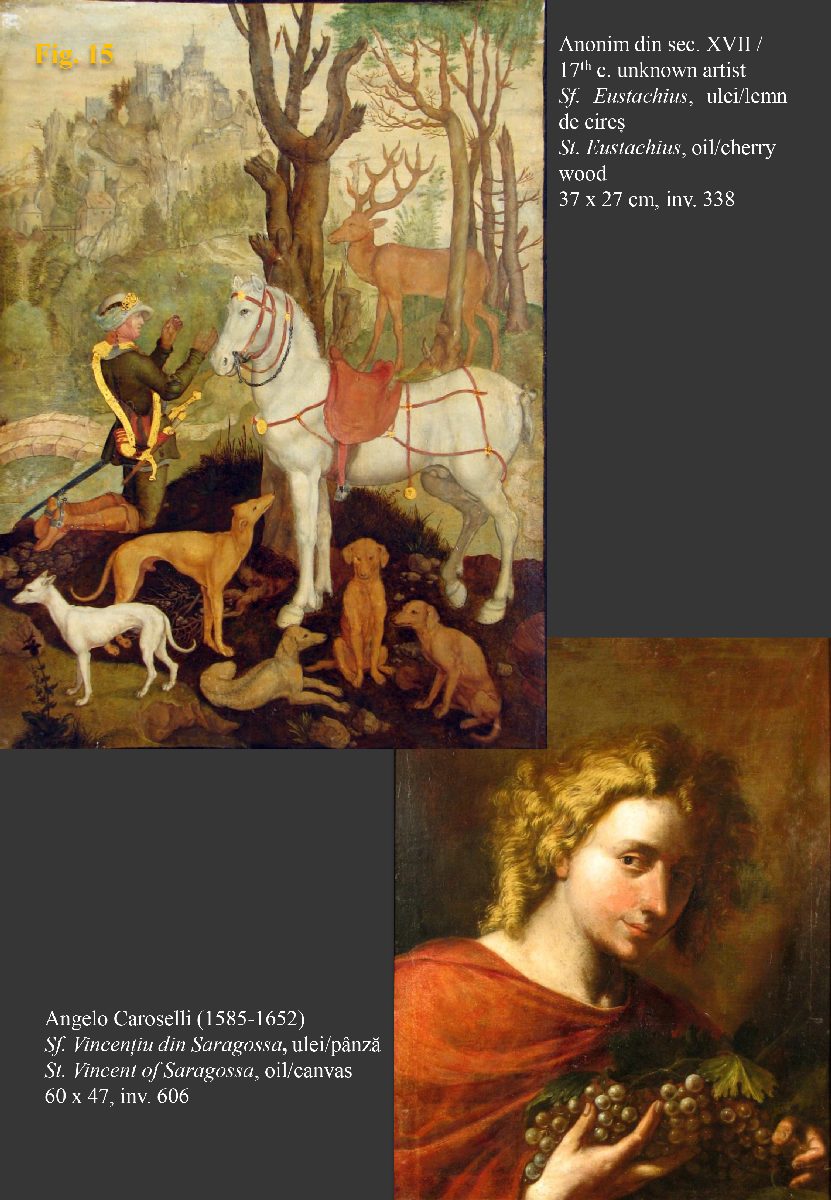

Also the historicity of St. Eustachius (Fig. 15) is doubtful, abounding in fantastical elements. Tradition describes him as a Roman general, converted after a vision he had on a deer hunt. As a result of his refusal to sacrifice to idols, he was martyred along his family by brazen bull at the command of Hadrian. The work in the Brukenthal collection is an anonymous 17th c. pictorialization after a famous engraving by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), dated ca. 1501. The composition illustrates the event that led to the conversion: the appearance of a stag with a crucifix between its horns and Eustachius is rendered as a hunter in armor.

According to tradition, St. Vincent of Saragossa (Fig. 15), considered the patron saint of winegrowers, was originally from Osca (Huesca, Spain) and was martyred in 304. According to A. Sonoc, the small work, painted by Angelo Caroselli (1585-1652), reflects a devotio moderna, being less related to the consecrated iconography of the saint: he is represented not as a deacon in liturgical vestments, but as a blond youth, with a red mantle (red martyr's dalmatic), holding in his hands 3 bunches of white grapes, with leaves, both hands showing only 3 visible fingers, a possible allusion to the Holy Trinity (although dogma was actually defined and proclaimed much later). With a kind, focused, slightly skeptical expression, without a halo, but standing out from the brown background through lighting and chromatic effects, the work can be compared with two representations of St. Zita in the museum's collection; it can be assumed that the painting was commissioned for a young vineyard owner or involved in the wine trade, whose name could perhaps even be identical to that of the saint, having him as patron from this perspective as well.

Martyrs of the Middle Ages are rarely represented in the European painting collection of the Brukenthal National Museum, only one work being certain. In a painting by an anonymous artist, The Torments of St. Livinus (Fig. 16) represents St. Livinus of Ghent (ca. 580–657), bishop of Dublin (656), then apostle of Flanders and Brabant. It is a copy from the 17th c. after a painting by Peter Paul Rubens (1633) in the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, not a pictorialization after a engraving from 1657 by Cornelis van Caukercken (1626–1680), also in the Brukenthal National Museum's collection (inv. no. V-31). During a sermon, St. Livinus was attacked by non-Christians who, before beheading him, tore out his tongue and threw it as food to a dog. The torturers wear costumes and pieces of weaponry specific to mercenaries from the 16th century, so the work can also be seen as influenced by devotio moderna; is a very possible allusion to the religious persecutions that began, ever since the spread of the Reformation, in the Netherlands, England and Ireland, both Catholics and Protestants resorting to torturing and killing missionaries.

Click an image below to open it